Australia’s iconic Great Barrier Reef is fundamentally changing because of repeated bleaching caused by high ocean temperatures brought on by climate change, according to marine biologists.

“It’s not a question of reefs dying or reefs disappearing, it’s reef ecosystems transforming into a new configuration,” says marine biologist Terry Hughes at James Cook University in Townsville, Australia.

“Species like fish and crustaceans and so on — the iconic biodiversity of reefs — all depend on the structure and three-dimensionality of the habitat provided by corals,” Hughes says. “When you lose a lot of corals, it affects everything that’s dependent on corals.”

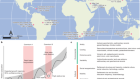

Corals become ‘bleached’ when stressed, expelling the colourful photosynthetic algae called zooxanthellae that live inside them and provide them with energy. According to a report released on 17 April by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority — the Australian government’s reef-management agency — the UNESCO World Heritage-listed reef is experiencing its worst mass bleaching event on record. The Reef Snapshot says that almost three-quarters of the reef is showing signs of bleaching and nearly 40% is showing high or extreme bleaching.

The report is based on aerial surveys of 1,080 of the Great Barrier Reef’s estimated 3,000 individual reefs, and in-water surveys of a smaller number of reefs.

Bleaching was observed along the entire length of the Great Barrier Reef, but was most severe in the central and southern regions.

“We’ve never seen this level of heat stress across all three regions of the Great Barrier Reef,” says marine biologist Lissa Schindler at the Australian Marine Conservation Society in Brisbane.

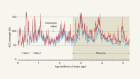

This is the fifth mass bleaching event on the Great Barrier Reef in eight years. Hughes warns that climate-change-driven increases in ocean temperatures are making it more difficult for the reef’s corals to recover between such events. “In the last six years, we’ve settled into bleaching every other year — in 2020, 2022 and now 2024 — and that’s simply not enough time for a proper recovery,” he says.

Global phenomenon

The Reef Snapshot was one of a series of coral-bleaching reports released this week that sounded alarm bells for reefs. The Australian Institute of Marine Science announced on 18 April that this year, southern parts of the Great Barrier Reef had experienced water temperatures 2.5 °C higher than historical summer peaks.

And on 15 April, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration declared that the fourth global coral-bleaching event on record is under way, with the Southern Hemisphere bleaching mirroring events seen in the Northern Hemisphere summer last year. It’s the second global bleaching event in the past decade.

Global sea surface temperatures broke records again in 2023, recording an average around 0.3 °C higher in the second half of 2023 than in 2022. The change was associated with a strong El Niño weather pattern.

“There have been very high temperatures driven by climate change all across the world, and there has been coral bleaching in many other countries,” says Roger Beeden, chief scientist for the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority in Townsville.

Hughes says the warming climate is reducing the amount of coral in the reefs, and the mixture of coral species is changing. For example, branching and table-shaped corals are often the fastest to recover from a bleaching event, because they are fast-growing, Hughes says. However, they’re also very prone to bleaching and have higher levels of mortality during bleaching events.

“It’s a bit analogous to a fire on land through a forest, that favours a bounce back by flammable grasses before the trees can recover,” he says. “Ironically, that bounce back, that resilience, undermines the ability of the reef to cope with the next inevitable bleaching event.” Seaweeds also flourish when corals degrade.

Beeden says that people who live and work on the reef are observing significant changes. “There’s historical photos that show inshore reefs that were laden with coral, and that’s very different now,” he says.

He says there are an estimated 450 species of hard coral on the reef, and such diversity means there is a chance the reef will adapt to the changing conditions, even if it changes character. “What we see within species is definitely there is variability in how they respond to stress events.”

Hughes says the solution to the Great Barrier Reef’s bleaching problem is clear. “Reduce greenhouse-gas emissions. Full stop.”

Controlling pollution and overfishing can help protect coral reefs — but it’s not enough

Controlling pollution and overfishing can help protect coral reefs — but it’s not enough

‘Ecological grief’ grips scientists witnessing Great Barrier Reef’s decline

‘Ecological grief’ grips scientists witnessing Great Barrier Reef’s decline

How climate change is melting, drying and flooding Earth — in pictures

How climate change is melting, drying and flooding Earth — in pictures

The ocean is hotter than ever: what happens next?

The ocean is hotter than ever: what happens next?

Can artificially altered clouds save the Great Barrier Reef?

Can artificially altered clouds save the Great Barrier Reef?

Fevers are plaguing the oceans — and climate change is making them worse

Fevers are plaguing the oceans — and climate change is making them worse

These corals could survive climate change — and help save the world’s reefs

These corals could survive climate change — and help save the world’s reefs